The water in Michael and Kelly O’Brien’s Longboat Key home was 4 feet above the baseboards after Hurricane Helene barged in.

With extensive flood damage, the O’Briens began the process of rebuilding their home on North Shore Road.

While they’re at it, they’re lifting the house 12 feet off the ground.

Michael O’Brien said he and his wife love the Longboat Key community and were willing to invest to save the house. They had workers tearing out drywall just days after the storm.

“The house itself is only 1,300 square feet, but the floor plan is what we really like. We remodeled the whole place over the eight years (since we bought it) and of course everything happened in September,” O’Brien said. “We love the house, and we felt this was the logical thing to do.”

The logical thing to do is a lengthy process with a hefty price tag. O’Brien said putting the house on stilts will cost $250,000, not including deck replacement, tearing up the driveway, and building a staircase up to the front door, but that it’s a worthy investment to protect their winter home from potential future flooding. The idea came to them via newsprint.

“We were sitting here in Milwaukee in January, and I’m reading the New York Times and there’s a full-page article on house lifting and I said to my wife gosh we should look into this,” O’Brien said. “They had interviewed a builder in St. Pete. We called them, got down there and met them and signed a contract.”

They expect to move into the raised house in January.

The O’Briens aren’t the only ones raising their houses on Longboat Key. According to town planning and zoning board director Allen Parsons, six permits have been applied for and issued by the town since August 2024 by residents wishing to raise their existing homes.

Chris and Sue Udermann had a difficult and emotional decision to make after heaping their belongings on the side of the road and ripping out the soggy drywall of their Helene-ravaged retirement home in The Village.

“We decided to go this route,” Chris said about raising the house 12 feet. They also considered selling the lot as is or repairing the house and selling. “It’s not cheap, but it’s probably the best for us to get it back to where we want it to be and have peace of mind that we’re not going to flood again.”

It’s quite the operation.

First, workers must disconnect the house from water, sewer, electric, and gas lines. Then, workers dig under the foundation of the house and place steel support beams beneath the concrete slab or wood frame that supports the house. Hydraulic jacks are placed under the steel beams and “cribbing” — a temporary wood support structure built around the hydraulic jacks — is installed. The cribbing is built up as the house is raised steadily. When the house is fully raised, “pilings” are placed as new, permanent supports for the raised structure.

There’s more than one way to raise a house, and several local businesses offer the service with varying methods. Roger Lusins, owner of RA Sarasota LLC, started a consulting/project management company with his wife, Angie, after their Longboat Key house flooded from a storm. They decided to build their house up during their rebuild, and the onerous nature of the process prompted Lusins to form a company to help his neighbors.

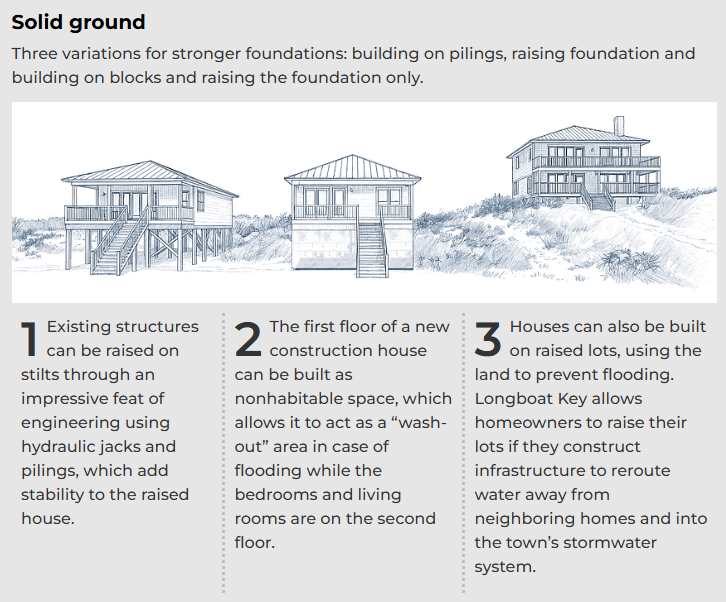

Solid ground

Three variations for stronger foundations: building on pilings, raising foundation and building on blocks and raising the foundation only.

“We flooded, and we grappled with ‘do we lift?’ As one of those people, I realized really quickly that there would be a need for someone who can just help people who don’t really know what to do,” Lusins said. “It’s an emotional decision, and we wanted to see how we can help and give good advice.”

Lusins said the price of raising a house varies based on the weight and size of the house, what piling method is used and what services are included by the house raising company (utility hookup, deck or stairway construction), but to expect a price tag starting at $175,000.

Right now, the Udermann house is 4 feet raised, and the two have been renting on the Key month to month because the process has been delayed repeatedly. They use a 7-foot ladder to get into the house if they need to grab something.

“This was our plan. We saved our whole lives and we always wanted to live on Longboat Key. This is the house we bought, and we thought this was gonna be forever, and then we flooded four times in three years,” Chris said.

Not being able to move in has been frustrating for them because the timeline of being back in their house was an important factor in their decision. This wasn’t a winter home for the two.

“It’s not a process for the faint of heart because there’s a lot of frustration, a lot of stress, a lot of anticipation,” Chris said. “Neighbors really helped out. There was a lot of support from our friends and St. Mary (Star of the Sea).”

Raising the lot

For some residents, tearing down their house and rebuilding after storm damage makes more sense than repairing and raising.

When doing so, in order to meet FEMA’s flood elevation requirements, inhabited areas of the house need to be elevated to a certain height which varies — depending on the location of the lot — from about 8 to 20 feet above sea level.

Eddie Abrams tore down his 70-plus year-old house in The Village. He and his son, Grant, are building anew next door to each other on raised lots. They had 300 truckloads of dirt delivered, compacting the soil after each load to provide the houses with a solid footing six and a half feet taller than before.

“We had to do something major,” Abrams said.

The first floors of the new houses will be a garage and storage space, meaning inhabited areas would be well above the FEMA-required elevation level. Parsons said the town does not issue permits for new construction that don’t meet those requirements to ensure the town can participate in the National Flood Insurance Program. That required elevation level can be found at longboatkeyfl.withforerunner.com.

Raising the lot isn’t cheap, but it’s cheaper than putting a house on stilts. Abrams, who is acting as a builder-owner for the project, said he thinks raising the lot will cost him about $100,000.

Blythe Jeffers and John Hodgson are also building up as they replace their Sleepy Lagoon bungalow with a bigger, higher and newer home. It gives them peace of mind.

“It’s been our permanent residence for the past couple of years but we want to make it last until well into the future,” Jeffers said.

So Jeffers and Hodgson did a combined strategy of raising the lot and raising their house. The road to their house has a 2.8-foot elevation, and their previous house was at 3 feet elevation. They had a foot of flooding during Helene. So when they were planning their rebuild, they decided to raise their lot so the bottom of their garage would sit at 6 feet elevation.

“The water line (from Hurricane Helene) matches where we are now going to have our garage floor,” Jeffers said. “Even if people put their house on stilts we are encouraging them to raise their lots with fill dirt to protect their cars as well.”

At the raised lot, five cinderblocks additionally raise the elevation of the home more than 3 feet. Doing all this comes at a cost — for fill dirt, drainage systems and extra blocks — that Jeffers and Hodgson think is well worth it.

“In the scheme of things, it’s a minor cost when you look at the overall cost of the project,” Hodgson said.

Jeffers said she hopes others on the north end raise their lots and house elevations, which could allow the town to raise its streets eventually in a proactive response to expected sea level rise.

“It behooves everyone to raise their lots on the north end,” she said, adding that people building now should be considering where the water level will be in 2070 because today’s new homes will exist then.

Stuffing styrofoam

When Hurricane Michael leveled Mexico Beach on the Florida panhandle in 2018, one home stood among the rubble, and Longboat Key residents noticed.

That house had several elaborate hurricane-prevention measures including the roof being literally strapped down and support piles submerged 28 feet into the ground to add stability. But what stood out to Jeffers, Hodgson and Eddie and Grant Abrams was the construction method: insulated concrete forms.

The process uses hollow foam blocks that fit together like Legos to form the exterior of the house. Rebar is placed and concrete is poured into the middle of the foam blocks, creating a stable structure that, according to a report by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, has “inherent strength” against strong wind gusts and greater wind-borne debris resistance in storms like hurricanes and tornados.

“It was really deciding that in order for us to bring our precious things here, we needed something that was more hurricane resistant than our cute bungalow built before the new hurricane codes,” Jeffers said.

The Jeffers and Hodgson house and both of the Abrams houses are using the ICF method. It’s more costly upfront — the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates ICF costs $3 to $5 more per square foot to construct. But there are advantages including lower insurance premiums, better energy efficiency and sound control.

“It’s more expensive because of the concrete. There’s a higher upfront cost just on the walls, but it pays itself back later,” said John Liptak of Insulated Concrete Systems, who is contracting with Abrams to build the twin ICF homes on Longboat Drive North.

After concrete is poured into the foam, drywall and siding is then drilled directly onto the foam, which acts as insulation. Abrams said the construction method will give him added assurance that his house will still stand if another storm rolls through. And being built on the raised lot, water damage will likely be avoided.

“It’s much more flood resistant,” Abrams said. “It’s a solid concrete house.”